AI, progress and happiness pt.1: the rise of the machines

Milan, Italy

May 6, 2016

I had the pleasure of participating in Milan’s FI-WARE VIP Bootcamp (4-6th May, 2016), under invitation by EBAN. There, along with several other investors and entrepreneurs, we assisted 15 startups from all across Europe to improve the structure and the presentation of their VC pitches.

AI as a danger

One of the people who actively participated, giving their full support to the event (and as a volunteer, nonetheless) was Federico Travella, founder and CEO of NoviCap, an extremely interesting venture in the “fintech” sector that came up with an innovative way of providing working capital for every kind of business. In discussion with Federico and other participants, the topic of AI was brought up, seen as a contributing factor to increasing unemployment, and through that, to social discontent and political instability.

Speaking at Milan’s FI-WARE VIP Bootcamp

I think it is clear that a major factor in the advancement of human civilisation, the very thing we define as our most important achievement, has been technological progress.

From the crude stone tools of our ancestors ten thousands of years ago, to today’s amazing technical advancements, we have countless tools are our disposal that make our life easier (and even extend it significantly) — while, at the same time, can also make it more dangerous (if they fall into the wrong hands, or are used for the wrong purposes).

The nuclear bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, perhaps the greatest technologically-assisted war crime in the history of humanity, made possible by the advancement of technology, teaches us, most explicitly, how technological progress can become a danger.

Even so, and despite the (always present) dangers, there can be no doubt that human civilisation is inherently tied to technological progress. Which makes technological progress not just a necessary evil, but a basic requirement for the very existence of civilisation.

21st century Luddites

A phenomenon as old as the Industrial Revolution (or even older), is that of the fear of progress, especially when it comes to its effects on the division of labor. Technological advancements often result in changing the ways in which certain tasks are performed, with the new way being more productive, but also requiring less, or even none, human resources.

We’ve seen, for example, farmers to protest the development of advanced farming tools, fearing that they will make them redundant, and the story has repeated itself with factory workers protesting against automation and factory robots.

The term “Luddite”, which today is levelled against anybody speaks against technological progress has its etymological origins in the struggles of 19th-century British weavers, who, under the leadership of the (mythical) Ned Ludd figure, destroyed the newly deployed mechanical weaving machines to save their jobs.

And while it is easy to laugh at 19th century protests against technology, the same phenomenon is possible to arise again in the near future, this time in white collar and office jobs. Only instead of mechanical weaving machines, it will be Artificial Intelligence that performs the same tasks faster, better, and more efficiently.

A categorisation of professions and tasks

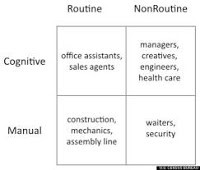

In the following diagram we can see an interesting categorisation of professions and tasks over two dimensions:

1. Whether they concern manual or mental labor.

2. Whether they require repetition or creativity

What we are witnessing today, are machines finally conquering two more categories: first those office jobs that don’t really require any inventiveness, through various software systems, and then the manual jobs that require some (but limited) inventiveness, with the introduction of “smart” robotic systems.

In any case, professions that are mostly based on intellectual capacity (but sometimes physical dexterity too), that require strong inventiveness and creativity, are still quite safe from automation. In fact, my personal belief is that some of them will never be performed better by machines, or at least not in the foreseeable future.

A recent revolutionary development

An impressive development that might point against my prediction above, has been the recent win of DeepMind’s AlphaGo software against the Korean worldwide Go champion, Lee Sedol (DeepMind, btw, an AI startup, was acquired by Google in 2014).

Why is that impressive?

Because the Chinese game of Go is so complex that it’s impossible for any computer to calculate in advance all possible moves in order to pick the best one (something that is still possible, after a little pruning of obviously bad moves, in Chess).

This means that a software playing Go has to “think” similar to the way a human player would, trying to figure which move appears to be better given its playing strategy. In a feat previously relegated to the realm of science-fiction, AlphaGo managed to “teach” itself Go, more or less like a human player would, but at a much larger scale and speed — by playing millions of games and studying countless previous Go matches.

In other words, it did what we would have done, but at CPU speeds — and the results were quite impressive: it managed to beat the world champion in 4 to 1, in a game that requires great mental effort and creativity.

So, if a program that can learn like we do, only faster, is possible, does that mean that we’ll soon be having software systems taking over creative jobs?

I wouldn’t hold my breath.

While the urge to generalise from that one feat is great, I believe that we’re still quite a long way from going from software beating humans in a specific board game (however complicated) to it being able to take over any intellectual / creative task.

That said, it’s absolutely certain that people working in highly intellectual and/or creative jobs, will soon have very powerful tools at their disposal — digital assistants that would help them do their job faster and better.

(to be continued…)

Dimitris Tsingos

Founder and CEO,

StartTech Ventures

P.S. This post is the first of a three-part series of posts in which I express my views and concerns about AI. If you’d rather read the whole thing now, it is available on Medium, where it was originally published.